The Transformative Power of Art: An Interview with Artist Fabrizio Ruggiero

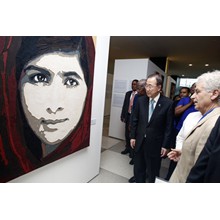

Fabrizio Ruggiero is an Italian artist and sculptor, renowned for his fresco paintings. In June 2015, Ruggiero’s collection of 16 portraits was part of the exhibition at the United Nations titled, “The Transformative Power of Art.” The portraits were of global thinkers and artists such as Pierre-Claver Akendengu, Maya Angelou, Joan Baez, Satyajit Ray, Audrey Hepburn, Vassily Kandinsky, Umm Kulthum, Gong Li, Miriam Makeba, Edgar Morin, Fatemeh Motamed-Arya, Okot p’Bitek, Sebastio Salgado, Wole Soyinka, Malala Yousafzai, and Ngugi Wa Thiong’o.

On June 23, 2015 in NYC during the exhibition at the UN, I had a conversation with Fabrizio about his work, study of Buddhism, upbringing in Italy, and love for India.

A: Tell me more about The Transformative Power of Art?

F: The exhibition is has 16 portraits of artists from different disciplines ,which include writers, singers, photographers and philosophers. The exhibition also shows how climate change is a global issue, central to human beings. I have displayed sculptures using natural elements like reeds and rock structures, so that they are like totems, sort of silent performers reminding us about what’s happening to humanity at this very moment- wars, famines, refugee crisis and so on. As a European, I know of boats from the African coast reaching Italy. We cannot take them all and hence we are not able to rescue them all. Among the portraits, there is this famous French philosopher. His name is Edgar Morin. He talks about culture and civilization. Culture sees each group as different. Civilization is something, which considers human beings as a whole. We should focus more on civilization to see ourselves as part of the humanity. There is a similar concept in Indian culture?

A: Yes, ‘vasudhaiva kutumbakam.’ The whole world is a family.

F: Yes, that one and in Greek philosophy, there was this concept of ‘Gaia’. Earth as a whole.

A: Talking about India, I was quite struck by the portrait of filmmaker Satyajit Ray and coming from India, it was a pleasant surprise for me. Have you watched his films?

F: Yes, some of them. I think he was in Italy. Say in 1950 or 60…There are similar kinds of movie makers in Italy who made films based on common life, common people and I could relate to it. And in 1972, I was traveling from Europe to India.

A: What were your impressions as an European arriving to India?

F: In India, when I was there for the second time in 2000-2003, I was working on this ‘Global Pagoda Project’ in Bombay. It’s the largest Buddhist Pagoda of the world under construction.

My initial association with India came through philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti. I think it was 1967 and I was 20 or so. A friend of mine took me to his speech in Rome. I was struck by his speech and clear mind. His words left an impact on me. In 1972, I was in Afghanistan, I was traveling. It was a crucial moment for me. I could go back to my life and my work in Italy, which was good financially but I felt caged there. So India was an expression of freedom. It was a very difficult decision. I was there for a year. Soon I saw myself spending summer in Italy and winter in India.

A: Interesting. So India might have been a second home to you?

F: (Smiles) Yes, I was spending lot of time in Banaras where I was studying Sanskrit. I was practicing Theravada Buddhism in India and Sri Lanka. That was freedom to me.

A: Has the stay in India influenced your art works?

F: Yes, definitely

A: What was the most pronounced influence?

F: I think in Italy, we have lot of history from the past- the Romans and so on. In India, I found the same. The place has a long history, which is still alive. Culture from past but which is living. That’s the most interesting thing. Now things are changing may be but still…

Apart from India, I like north Pakistan and north Afghanistan because it was the home of ‘Gandhara’ school of art, the Indo-Greek culture, which to me was a positive moment in human history. Cultures from different parts of the world living peacefully.

A: The theme takes us back to the UN exhibition again. How was the project commissioned? How did you get this great opportunity?

F: Yes, I have been working a lot on the relationship between different cultures. Last year, I was curating a permanent exhibition at the National Museum of Cameroon in Africa, in the capital city of Yaoundé. It is a very interesting project because it speaks about the friendship between an Italian explorer -his name is Pietro Savorgnan di Brazza, who by the end of 19th century went to explore the southern part of Congo River. He became friends with the local king who was called Makako. Pietro is still well remembered with friendship and reverence among the local people. This Italian explorer might be the only one who went to Africa without fighting, shooting and without making slaves and so on. For this reason, it is a nice example of how different cultures can be brought together. While curating the exhibition in Cameron, I met few officials from the UN who later came to visit my studio in Italy and they said that they were interested in this theme of the link between various cultures.

A: Is there a similar theme of coexistence among the 16 portraits at the exhibition – of artists and thinkers from different countries?

F: These portraits show people who gave voice to the voiceless…all of them worked in different ways to uplift them.

A: The main characteristic of most of your art works is the fresco style. Was there a reason why you chose this particular style?

F: Yes. When I was young, my father used to take me to the National Museum in Italy, in my hometown of Naples. Naples is close to Pompeii., a town which was very rich and flourishing from the Roman Empire and was right underneath the volcano Vesuvius. When there was a volcanic explosion, the ashes buried Pompeii. In the 18th century, they dug out the ashes and found the city intact. Some of the fresco paintings from Pompeii were brought to the museum. While my father told me the story of the volcano, I was more attracted to some of these shining pieces of glass or things inside the very surface of the paintings. I found this kind of painting very attractive to the eyes. Fresco is also the main kind of painting in the Italian Renaissance. Then with the beginning of 20th century, with the rise of modern art movement, all these were rejected.

A: Talking about fresco, what was “architectura picta”, the workshop you organized in Tuscany, about? I read that it was a fusion of fresco and modern technology.

F: Yes, you can find fresco style in Rome, Florence, and also in the south of France. You make this mortar out of lime plaster and sand, which is then applied to the walls. When it becomes dry, it appears like marble. And natural mineral pigments are soaked in. This is durable and lasts longer. It is interesting to understand how the colors that were used in the Renaissance are so eye catching. It is a tradition that is most lost. I was trying my own ways and combinations to find this out. Then the problem became that people actually end up painting on the walls. I was looking for some alternative and I found that with modern technology, it is possible to build many thin layers of fresco that can be easily be moved from one place to another. This is what we did in ‘Architectura Picta.’ The exhibit at the UN also used this same technique.

A: A sense I get from talking to you is your belief that art can transform lives…

F : The 16 portraits… They have been an inspiration to many people, as they wanted to bring peace in this world. So in this sense, from my point of view, art can influence people in different ways. I am a visual artist, so I will speak about it from that side. I think the energy that an artist puts into a painting or art work in a certain way reverberates and goes back to those who are looking at it. So it is very important what kind of energy the artist puts in. It is difficult to express it. So when you look at a painting, if it gives you something beyond words, that insight is important. In Latin, it is called ‘parerga’- which means accessory [the unseen that burbles out of a major work].

A: Thank you so much for your time and this great conversation.

F: I very much enjoyed this conversation.